On Insomnia

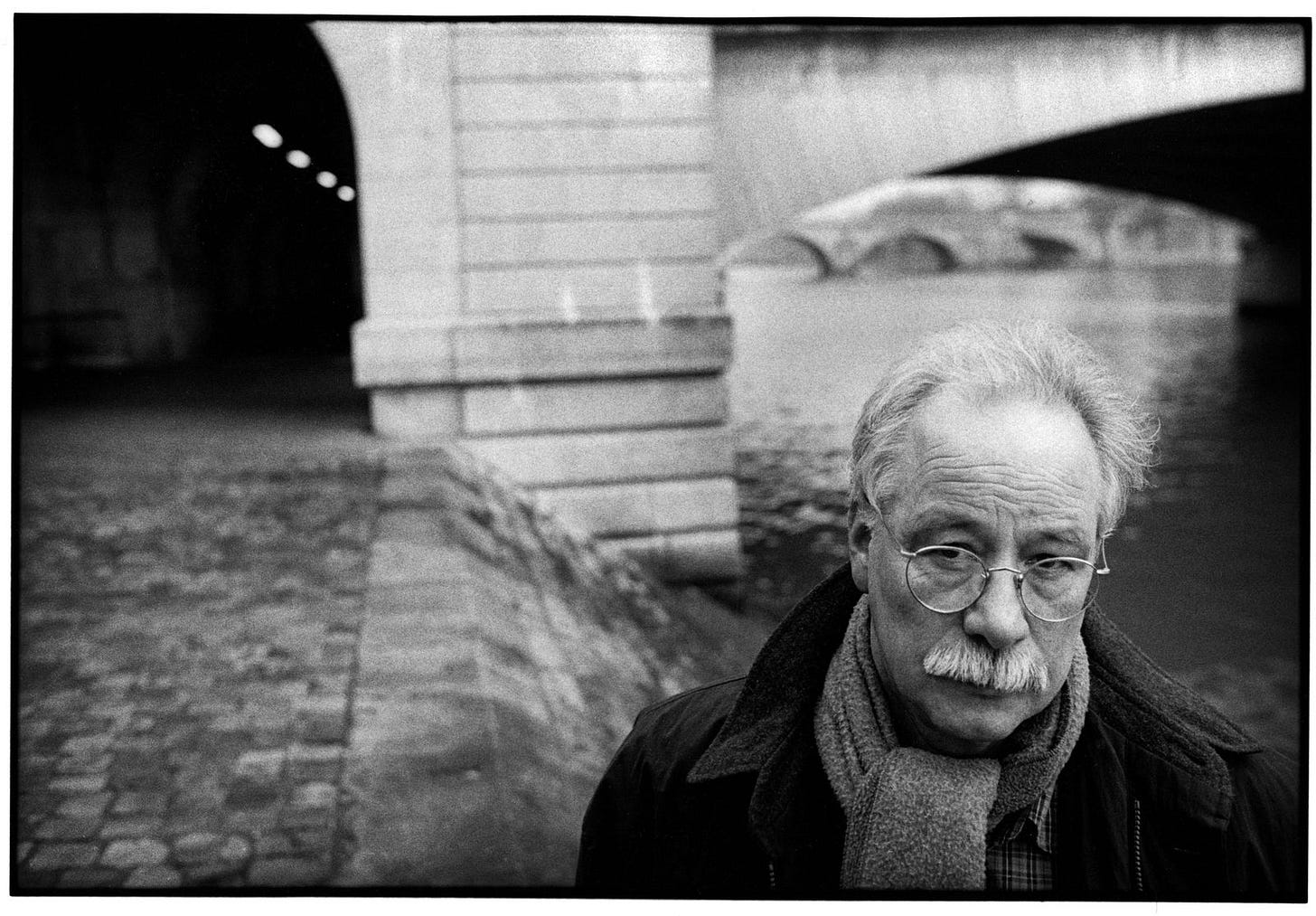

Sebald and Blanchot

If you were only to read my personal essays, you would be forgiven for supposing that I’m a rather dreary individual. So many of them obsess over loneliness and regret and addiction, that it appears I have nothing positive to say. Of course, the fact of the matter is that I am a rather happy person. Things are ‘going my way’ at present, personally and professionally. It is only that this must be an active sentiment, that it must be articulated, for myself as much as for anyone else. This is because where I remain passive it is also true that I propend towards depression. Where I allow the world to unfold on its own terms it appears cast in a rather dim light. Astrologers would say that I am ‘under the Sign of Saturn’, a kind of melancholia. Jung would probably say that I am unindividuated, that I have repressed or negative functions that have not been properly psychologically integrated. So much to say that the natural cast of my thoughts is not positive.

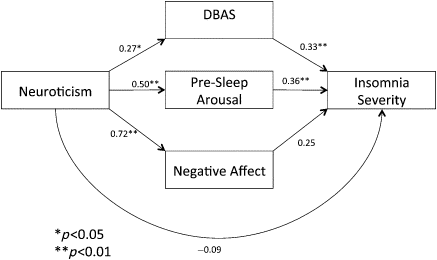

There is also a quite banal explanation insofar as my mental health is downstream of physical phenomena. I have, since I was a very small baby, often been sick and I have always suffered from nightmares and recurrent bouts of insomnia. There is not much predictability as to when these phenomena will manifest and so degrade my quality of life, which then logically affects my perception of life generally and so, terminally, the particular content of my essays. The genesis of this essay is that I slept all of an hour the night prior to writing it. To be a little more specific about what I mean, night terrors specifically occur almost exclusively in children, but where they are sustained in rare instances into adulthood -as in my case- they are highly comorbid with depression and with neuroticism.

About a month ago I pulled a chest of drawers onto myself because, in my confusion between wakefulness and dream, I feared I was trapped in a submarine or a dungeon and tried to pry open their doors, only to pull a heavy piece of furniture atop me. That fundamentally ruined my week. But it all sounds so terribly fake, I’m aware that teenagers claim these sorts of disorders as a badge of honour, that they’re ‘so different’ and ‘so haunted’. But it is not at all something to be desired: it makes me not a little dysfunctional, a little unpredictable, and probably not an altogether wonderful person to share space with over an extended period.

The narrow end of which is that, given the bulk of one’s intellection is likely drawn from the passive state of their thoughts, rather than the active and interrogative state, the subject matter I am most drawn to writing about is most likely to be that characterised by negativity, which so characterises my life. I would find it difficult to write one of those innumerable Substack essays on, say, how to be more productive or how to read difficult books or how to see beauty in small things, because I’ve just never really thought about things in that frame of mind. You might say that I rarely ask how, but rather why? Why are things as they are? Moreover, this is obviously conducive to reading certain kinds of literature, which is where we will be taking this slight reverie next.

After I had come to terms with the fact that I would not be sleeping gainfully that evening, at around 2:30 AM, my mind began to wander. It recalled W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, which begins with our pseudo-Sebaldian narrator drifting in and out of sleep at a clinic for the mentally disturbed following the deaths of two of his colleagues and friends. In theory he then proceeds upon a walking tour across East Suffolk, but there is not really any reason to suppose that he vacates the clinic’s bed in the first place, because the character of his hike is at once lucid and fatally digressive. A midtrek lodging in an impoverished Suffolkian town recalls the collapse of Old Dunwich into the North Sea, what was once the enriched capital of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom. And then looking out over the North Sea recalls various artefacts previewed in the empty, apathetic cities of the Netherlands. The Taiping Rebellion, Joseph Conrad, the history of European sericulture, destructive hurricanes, paintings of anatomical dissection, Catherine of Siena, to name hardly a handful of things Sebald touches upon. The following passage is illustrative:

As I sat there that evening in Southwold overlooking the German Ocean, I sensed quite clearly the earth's slow turning into the dark. The huntsmen are up in America, writes Thomas Browne in The Garden of Cyrus, and they are already past their first sleep in Persia. The shadow of night is drawn like a black veil across the earth, and since almost all creatures, from one meridian to the next, lie down after the sun has set, so, he continues, one might, in following the setting sun, see on our globe nothing but prone bodies, row upon row, as if levelled by the scythe of Saturn—an endless graveyard for a humanity struck by falling sickness.

And while I doubt I should ever be as articulate as Sebald this does match the experience of my restless mind, there upon the bed, the covers pulled over my head. Because the mind cannot help but make neurotic connections between sensation and memory and fiction. I close my eyes, and the phosphenes there take on the silhouette of a city I have never seen from a vantage I would deem impossible. A city of steeples and slanting rooftops, mere outlines, obviously not Australian for how old and weathered they look. And then my mind will take an orthogonal step and a terrace becomes the movements of a chess board, the Dragon Variation of the Sicilian Defense or the Soller Gambit. From this I will wonder about the contents of Stefan Zweig’s Schachnovelle, which I do not own, and from that German invocation I will try and calculate the unfolding narrative of Robert Walser’s The Assistant, which I do own but have not finished. Then a tricky theological question might present itself, or I will wonder if I have been good to women in my general dealings or if I am as terrible as I fear I may be. Then my mind’s language will cycle from the linguistic to the auditory and I will hear narrow passages of jazz arrangements in a Launceston café dating to fifteen years prior that I know I will never, ever identify, and then I will bemuse myself by imagining what a striking figure Sir Arthur Haselrig must have cut, wearing a full set of plate armour in the midsts of the English Civil War when most had dispensed with such pageantry. Then my brain will steep itself in memory, a younger self, lying upon a couch in the church lobby where my mother worked as a secretary, following a concussion at school. She had collected me from the pavement. I had learned in short order that you should not fall asleep when concussed, because you will not wake up, and it was then that I first tried to will myself to sleep. So the night unfolds, and there will be no end until sleep really does take me.

This is, on one level, a waking nightmare. The distinction between what I would have expected that evening and what manifested is quite neatly captured by Blanchot in his essay The Outside, the Night:

The first night is welcoming. Novalis addresses hymns to it. Of it one can say, In the night, as if it had an intimacy. We enter into the night and we rest there, sleeping and dying.

But the other night does not welcome, does not open. In it one is still outside. It does not close either; it is not the great Castle, near but unapproachable, impenetrable because the door is guarded. Night is inaccessible because to have access to it is to accede to the outside, to remain outside the night and to lose forever the possibility of emerging from it.

Blanchot is always mysterious, but the clarified point he is making (in quite figurative terms) is that there is a night where one finds peace and one that is restless, that cannot even offer a restive death. It strikes me as queer that, though he draws upon many sources for this essay, he does not once consider the question of insomnia, bar implicitly, which seems to square most easily with his conception of that ‘other night’ (Although he does touch upon insomnia in a later essay, Sleep, Night). At one point Blanchot suggests that whomever is subject to that other night senses that they are approaching its heart, the essential night of sleep and death, but it is at that moment that he will lose sight of it, and remains inessential and impossible. And that was very much the pain I suffered last evening, always drifting towards but never reaching the shore of sleep, like a ship caught in a perpetual rift.

And the trouble with this phenomenon is that I cannot really say anything conclusive about it. Only that I identify with it in these two minor examples, as I do in the works of Proust or Juan Rulfo or my dear Gene Wolfe, and that should I suffer this fate for a sequential night, I am sure that this will be where my mind will drift.

⁂

Note: I preemptively disown any grammatical errors or logical non-sequiturs that have elapsed in the process of writing this sleep deprived essay.